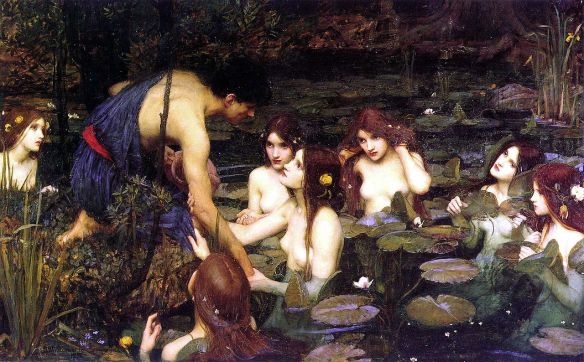

Hylas and the Nymphs, Waterhouse (1896), Manchester Art Gallery Public Domain

In Greek and Roman mythology, the Naiads are interesting, unsettling characters. They presided over water and lived in proximity of ponds, fountains and rivers. Similarly to the element they controlled, their nature was fluid and sometimes overwhelming. Naiads could be very dangerous maidens, as some ancient young men learnt. Take for instance the nymph Salmacis. As we read in Ovid, she fell in love with Hermaphroditus, the son of Hermes and Aphrodite: the boy tried to resist her, but ended up raped in the water. As a result of Salmacis’ prayers, the two were transformed into one intersexual being. And what about the fate of Hylas who, mesmerised by the Naiads, disappeared and never went back to his companions, the Argonauts?

As it has often happened to powerful and unsettling women in the course of history, the Naiads have been silenced in the occasion of a performance, which took place about one week ago here in Manchester. As part of a forthcoming exhibit of Sonia Boyce, the artist and the exhibit’s curator, Clare Gannaway, have decided to remove the painting Hylas and the Nymphs of J.W. Waterhouse from the Gallery, and asked visitors to intervene on “tricky issues about gender, race and representation” by posting opinions on the empty wall .

Unsurprisingly, the event has sparked polemics, since the painting is a very loved ones (even postcards were taken away from the Gallery’s shop), and the topic is hot after the #metoo campaign and the appalling facts that injected it. So yesterday I visited the City Art Gallery, as many other times since I moved to Manchester. As required (I am a good and engaged citizen), I left my message, which you can download: Art Gallery Comment. In front of that wall I felt uncomfortable and sad, as a classicist and as a feminist woman. (There is a lot to be said about race too, but I will leave this to another post.)

Before starting explaining why I am uncomfortable, allow me to comment briefly on the installation’s lack of aesthetics, considering the mess and the poorly written intention sign displayed on the wall. I do not know what is wrong with curators’ tastes these days, it must have to do with government’s cuts I guess (?): professionals in art galleries seem unable to use decent materials, fonts, etc. This is not the first time I have noticed the trend. Anyway, never mind.

Let us move to discussing the uncomfortable classicist. The study of Classics is under attack in this as other countries: to those in charge of education policies, it seems an irrelevant subject, useless in terms of job skills and employability. While statistics actually contradict this view – but numbers are tricky and I don’t want to go there – there are good reasons for criticizing the way Classics has developed as a discipline deeply rooted in colonialism and cultural elitism, especially in the context of the very classist British society and its education system. Nonetheless, as recent studies have brought to light and some new ways of practicing Classics show, it is a discipline that nowadays gives space, sometimes with hesitation, to multiple voices in terms of identities, methodologies and topics. Our contemporary culture is deeply entangled with antiquity and eventually the problem is not the content of Classics, but rather the way that content has been used, misused and manipulated in the course of centuries.

In fact this performance is a great example of how Classics has been misconceived, erased and neglected to the point that the curator and the artist seem completely unaware of the semiotic of the painting, otherwise I am sure they would have chosen another one among the many others displaying eroticised young female bodies in that room.

A Guardian’s commentator has defined the painting as ‘semi-pornographic’. But what does ‘pornographic’ even mean, considering how female, male and intersex bodies have been reproduced and objectified in the course of art history? One can only view this painting as pornography if completely unaware of the semiotics of displaying beautiful naked body in art history. Moreover, isn’t it the role of art to make the viewers uncomfortable, having unexpected reactions, and thinking about them? Curatorial tastes and practices as those behind this installation seem to me more Victorian than those of the Victorians they pretend to criticise. How can you have a meaningful and informed debate on displaying gender without knowing the historical development of producing and displaying gender in art?

I am moving now to the woman who feels offended by this superficial cultural operation. Women have been oppressed, beaten, raped, unpaid or underpaid for their work, and discriminated in other various manners. In the course of history, women have also found different modalities to negotiate their way through family, work, basically life survival: they have played the game according to rules which were imposed by men, and I believe that some inversion myths like the one of Hylas and the Naiads, in which females are controlling if not raping men, tell us a lot about the violent terms of that negotiation. Men felt uncomfortable in front of women’s body and beauty, and interpreted these problematic, threatening feelings as the result of a female power that if unleashed could lead men to lose their minds (very contemporary, I know: that’s why Classics matters). Should women forget all this past just because we now want to be appreciated as persons with many more skills than just beautiful and powerful bodies? I do not think so: I do want that story to be remembered and understood for its multiple meanings and for the oppressive social structures it has contributed to produce and reproduce.

I do not want the Naiads to be silenced. I want a society inhabited by citizens of any gender able to deconstruct the long history of a myth and its representation in art that enlighten the strained, violent relationship between women and men in the course of centuries, including our very present. In particular, I want strong women, proud to have survived that past (yes: we are all survivors as recent horrible facts constantly remind us) and ready for our turn to be in power, and hopefully change the way power has been exercised so far. In fact new Naiads are here, they are taking over, and nobody will be able to silence them again.