Last Thursday, The Guardian published a riveting report of the ongoing papyri crisis. Charlotte Higgins has written a compelling and remarkably clear piece, finding her way through the intricacy of the events. From my point of view, the most interesting part is the revelation that my colleague Mike Sampson will soon publish an article about a Christie’s private-treaty sale brochure that an anonymous academic source passed to him. As Mike has kindly shown me some of his material in advance, I went back to a conversation I entertained with Christie’s from 28 November 2014 to 15 January 2015. In the light of what has now emerged, in my opinion this conversation opens further questions and doubts on the newest Sappho provenance narratives, and more broadly on the mysterious ways in which ancient manuscripts move on the market.

But before delving into this epistolary, it is necessary to recap a number of facts, including some that Higgins had no space to discuss in her article but which are crucial for the points I wish to make here. As my readers know, I came to the Green mess in early 2014 not because of the Christian papyri, but indeed because of the newest Sappho fragments: P.Sapph.Obbink (in anonymous hands) and P.GC. inv. 105 (in Oklahoma City, with Hobby Lobby). However, I was soon intrigued by the whole Green endeavour, and one of their papyri, in particular, captured my attention: a small Coptic fragment with lines from the letter of Paul to Galatians, GC MS 462. As I will show in the following, this papyrus story interweaves with that of the Sappho fragments so intimately that if one forgets it, there’s the risk to miss the level of misinformation and deception disseminated (voluntarily or not) in the course of these years.

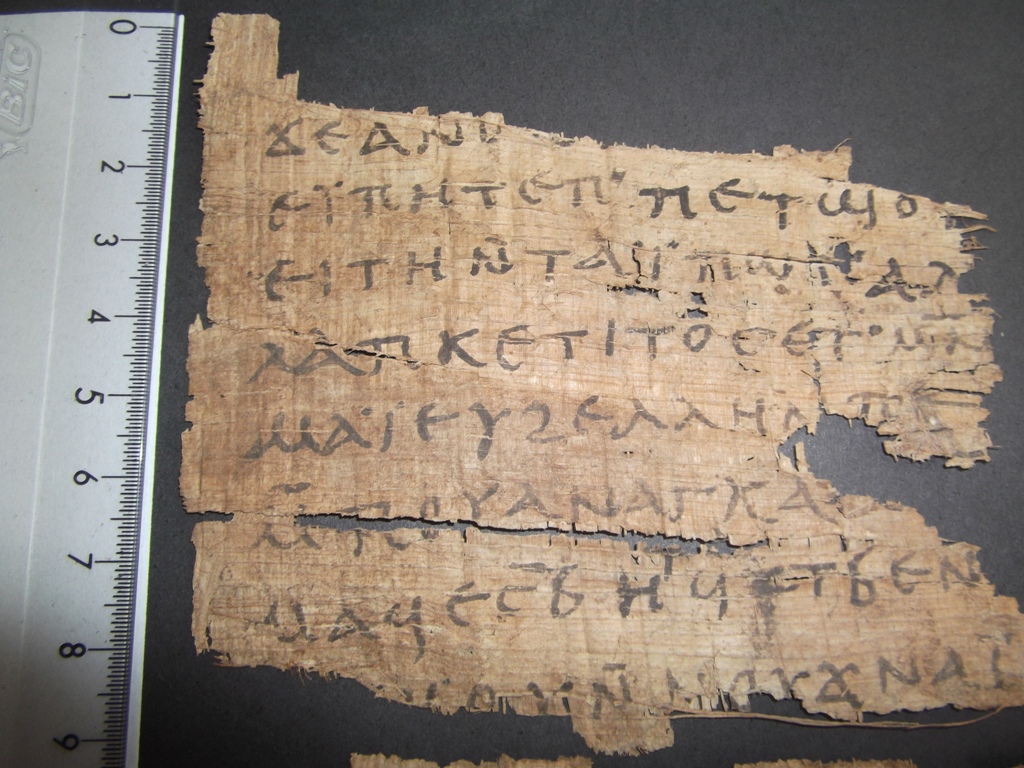

The Galatians 2 Coptic fragment when advertised on eBay

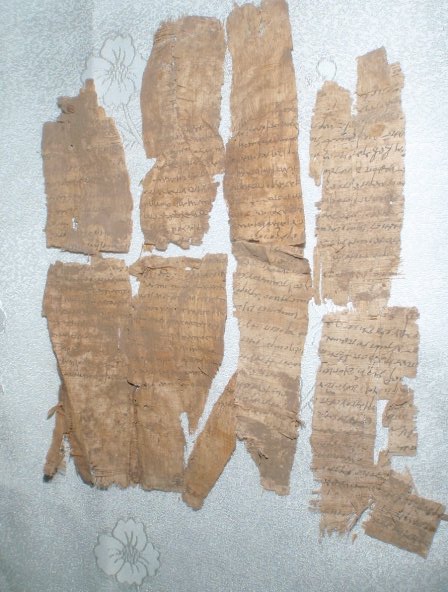

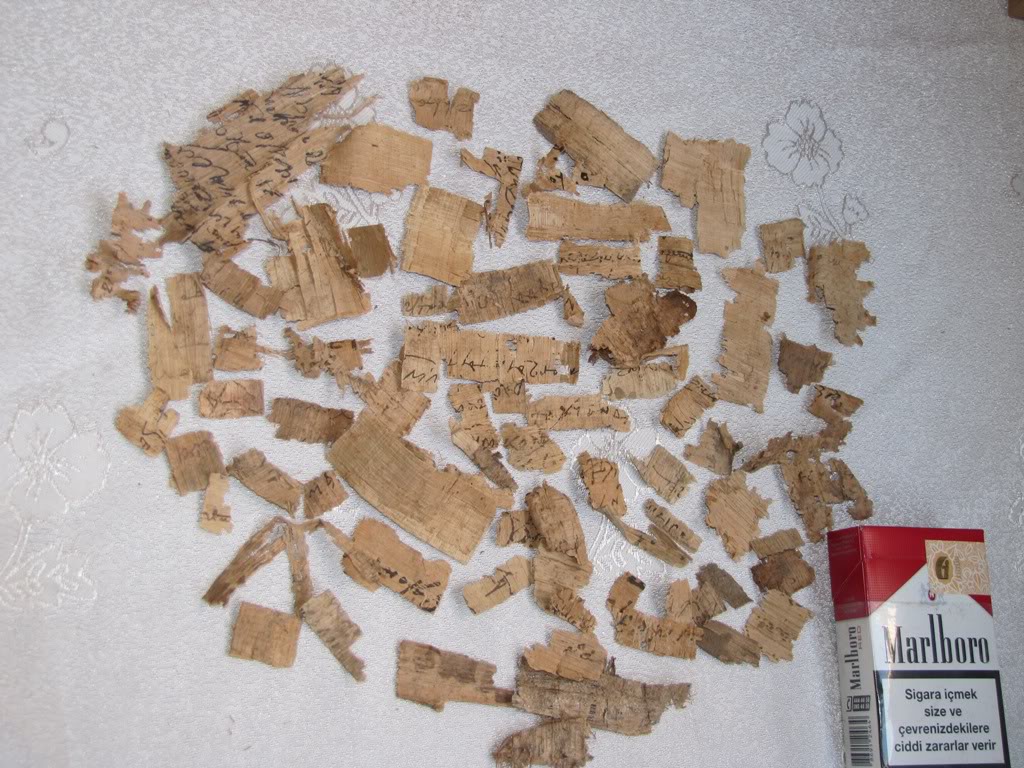

Let us start from the beginning. In February 2014 we were informed of the existence of the newest Sappho fragments without being provided any firm detail and clear evidence about their provenance. Most of us were completely unaware that since 2009 an American millionaire was hunting through the manuscripts market for the joy of dealers and some academics too. As I became intrigued by this multifarious crowd, the following April I went to visit the Green exhibit, Verbum Domini II, at Vatican City where I spotted our Galatians Coptic papyrus and immediately realised that it was the same fragment that in October-November 2012 was offered on sale through a Turkish eBay account called MixAntik. At that time, MixAntik was operating in violation of Turkish law for the export of antiquities and never provided any documented provenance for that or any other fragment sold in the course of the years. I asked David Trobisch, the newly appointed director of the Green collection, some questions on the papyrus origin: did the Green buy Galatians on eBay? His answer was that he was new to the job and the Green files were in such state that he was unable to provide any information at that stage.

The first big turn in the Sappho and Galatians provenance tale happened the following autumn of 2014. Right before a session on issues of provenance organized by the Society of Biblical Literature at the Annual Meeting of San Diego, I was timely informed by Trobisch (my respondent at that panel) that the Green Sappho and Paul Galatians fragments came all from a lot sold at auction by Christie’s London in November 2011 (I duly reported this after the conference in this blog post). Dirk Obbink – Trobisch added – would have provided full details on the recovery of the Sappho fragments in a forthcoming paper to be read at a conference the following January. Right back from San Diego I started a conversation with Christie’s (28 November is the date of my first email), as I was completing an article on all these and other matters (later published in the Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists), and wanted to have my facts straight.

January 2015 came, and Obbink’s paper was not only read to the Annual Meeting of the Society for Classical Studies, but also disseminated online (it is still available from here). The key section about the Sappho provenance was this:

“As reported and documented by the London owner of the ‘Brothers’ and Kypris Poems’ fragment, all of the fragments were recovered from a fragment of papyrus cartonnage formerly in the collection of David M. Robinson and subsequently bequeathed to the Library of the University of Mississippi. The Library later de-accessioned it in order to purchase Faulkner materials. It was one of two pieces flat inside a sub-folder (folder ‘E3’) inside a main folder (labelled ‘Papyri Fragments; Gk’), one of 59 packets of papyri fragments sold at auction at Christie’s in London in November 2011.”

Then the article placed the papyri in question in the Arsinoite, furnished some bibliography and also the name of the Cairo dealer who sold papyri to Robinson in 1954, Sultan Maguid Sameda. As for the Green fragments, the author explained:

“A group of twenty-some smaller fragments extracted from this piece, being not easily identified or re-joined, were deemed insignificant and so traded independently on the London market by the owner, and made their way from the same source into the Green Collection in Oklahoma City.”

The paper was later published in the form of an academic article (“Interim notes on ‘Two New Poems of Sappho’”, ZPE 194 (2015), 1–8) and the story repeated more or less in the same way in an interview to Live Science. (For more details on later sometimes conflicting versions, check out Brent Nongbri’s blog, and Uhlig and Sampson’s recent article for Eidolon).

Most believed the narrative, but for me it remained still problematic because neither the author nor the owners provided any solid document to support the purported collection history. On top of this, the Green Galatians fragment had been said to have the same provenance too. I had difficulties believing that someone had bought a lot of papyri at Christie’s in 2011 with a potentially good provenance, found a fragment from a letter of Paul and then a year later offered it on sale not through Christie’s or any other main auction house or dealer but rather through a most bizarre eBay account. Moreover, MixAntik never mentioned a Christie’s auction–why not? It would have provided plausible provenance. In a story full of morons like this one, random silly behaviour is always a possibility. Still, I wonder…

Anyway, after Christmas holidays and some reminders, on January 10, 2015 Donadoni finally sent me the following information about both Sappho and Paul:

“These were part of a large collection of cartonnage fragments – they weren’t individual papyri whose texts could be identified. As Dr Obbink explained yesterday [Obbink read his paper at the conference on the 9 January], the Sappho fragments were recovered from cartonnage that we sold in 2011 – ie [sic] layers upon layers of recycled strips of papyrus glued together to be used as book bindings or mummy coverings. Some of these strips may have had text on them – often legal texts, shopping lists, or receipts of little value. But the only way to recover them and to identify the texts that aren’t immediately visible is to soak them in a warm water solution and chisel away at the layers. You will understand that when we receive such consignments, we sell them as they are, and identify what we can: we do not and cannot have the capabilities to dissolve other people’s property in the off-chance we may discover something of note.”

To this I answered asking if Christie’s had pictures of the cartonnage as it was when consigned for the auction. On January 13, Donadoni explained: “There are no further images beyond what is already shown in the 2011 catalogue.”

As many know, first and foremost the poor Green crowd (they are martyrs in this respect, I assure you), I can drive people crazy with my stubborn questions. In fact when I insisted again asking how the hell was Christie’s sure that these fragments came from that lot since they only saw layers of compressed papyri, a rightly exasperated and mad at me Donadoni concluded (14 January 2015):

”I am sorry if I have not been clear. I’ll try to be as concise as possible: I confirm that we are not simply relying on the word of the collector. The provenance is as stated. There is no doubt that the specific pieces came from the cartonnage that we sold in 2011, there is clear evidence to that effect. They were not identified at the time because they needed recovering (and thus dissolving in a warm-water solution) or piecing together from a myriad of tiny fragments.”

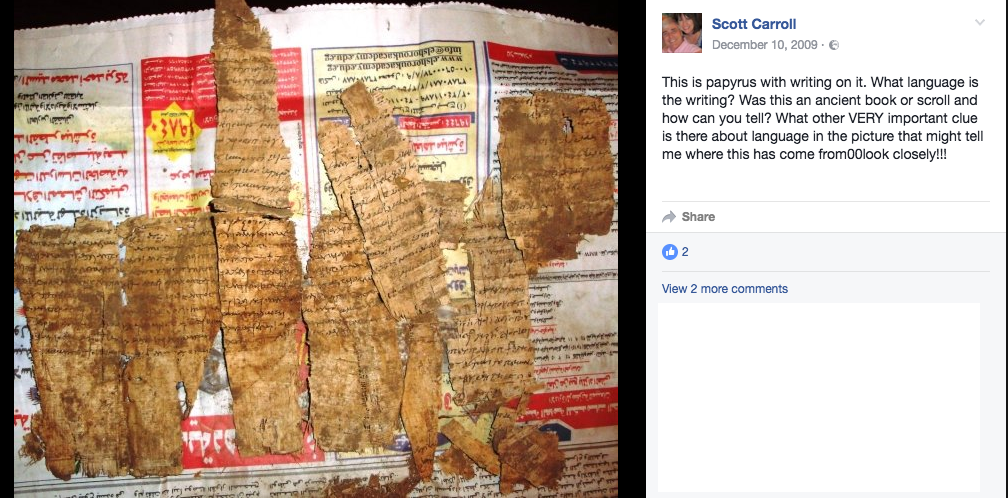

But now that we have seen the private sale dossier, I would ask Christie’s: What is the ‘clear evidence’ that they had but that nobody else was able to see? Is it perhaps the layered papyri cartonnage, which is reproduced in the pdf brochure? Did they take that picture in house? That picture, in particular, seems at odds with their repeated statement that there was no other image besides the one in the catalogue: Is there a simple explanation I am unable to understand? This is all very confusing, you would agree. I find interesting that according to Sampson’s metadata analysis, Christie’s brochure in its current version was pulled together roughly between 13 January and 26 February 2015 – more or less while I was entertaining these email conversations with Donadoni – using a version created before, in 2013. As Higgins reports too, the date of the Sappho ‘cartonnage’ digital shot is instead 14 February 2012, seven days after Scott Carroll had already shown the Green Sappho fragments in their shiny glass frame at one event in Atlanta, as documented in a video (https://brentnongbri.com/2018/12/13/the-green-collection-sappho-papyrus-some-new-details/). Is anyone able to explain how this happened?

In the Green quarters, however, details of the provenance story of their Sappho and Galatians fragments were destined to change dramatically. In the summer of 2017, on the wake of the Iraqi tablets scandal, the Coptic Galatians papyrus was again under the spotlight, and in a much more problematic way for the Green. The year before, I had discovered by pure chance the identity of the man behind MixAntik (morphed into ebuyerrrr in the meanwhile), reported it to eBay and the police since he was still selling unprovenanced papyri, and received unpleasant threats as a result later on; meanwhile the investigations of Candida Moss and Joel Baden, reported in their book and magazine articles, demonstrated that there had been many more Green acquisitions from Turkey and Turkish sellers, with meetings in Istanbul and London too. In short, it turned out that a certain number of the Green papyri came from MixAntik aka ebuyerrrr and close sources (for more details, see my chapter in The Museum of the Bible: A Critical Introduction. Fortress Academic).

On 20 July 2017 The Times informed that Egypt had started an investigation on the whereabouts of the Coptic Galatians fragment; asked for comments, Trobisch still referred to the trusted dealer and the Christie’s auction story. But the following autumn, that story evaporated. On November 17, 2017 The Chronicle of Higher Education posed a similar question on Galatians to the newly appointed director of the Green Scholars Initiative, Mike Holmes:

“It was bought from a dealer in good faith, and the dealer provided certain information,” says Holmes. “That information turned out to be incorrect.” Whether that dealer purchased the fragment from eBay is still unknown, according to Holmes. As a result, he says, it won’t be seen in the museum.

To my knowledge, Christie’s has never commented on this incredible turn of the story: How do they explain all this? Were they also said something that they just believed? Perhaps the Green trusted dealer was the buyer of the famous 2011 lot 1 and Donadoni had no reason to doubt their word? Who knows? I confess I feel lost.

Anyway, if Paul and Sappho go together – as I thought at the time – then the provenance of the Green Sappho fragments should also be under revision, but when I asked the Green (i.e., Trobisch, Holmes, and also Jeff Kloha), the answer always was that documents were insufficient or lacking at the Hobby Lobby archives. To be thorough, in our last email exchange of last July, David Trobisch wrote me something notably different, that is: ‘I’m surprised to hear that you think the Sappho fragment came from the same auction as the Coptic Galatians fragment.’ In total dismay, I reminded him that he officially said that in many occasions, including to The Times. Was he possibly ironic? I never received an answer back. Bless him. On the contrary, I always received answers from my lovely friend Mike Holmes, a Green man I trust, and his last words on their Sappho fragments last summer were:

“It has not been possible to identify the seller of the Sappho fragment[s] at this point due to the lack of consistent record keeping and vague invoices in the early years of the collection. The Sappho fragment is not listed as a specific item on any invoice in museum records”

And here we are, my friends, stuck in between a flood of missing paperwork and the secrecy of Christie’s and the antiquities market sales, which are protected by current laws: privacy and non-disclosure are perfectly legal. What will happen now? Who knows…! The Greenery has started an internal cleaning exercise, the outcomes of which are, however, still unpredictable and controlled by a platoon of lawyers; on the other hand, we don’t know anything (yet) about the owner or owners of the largest Sappho fragment and their thoughts on this mess. I think they must be nervous as they paid a fortune (around £ 800,000 is the guess of a Guardian informed source) for a lovely manuscript (the case in the Christie’s brochure though, ma che brutta and a bit vulgar! I hope they found a new one), which however turned out to have a provenance background with some grey areas. As a result, the market price must have definitely lowered down in the meanwhile. In case the grey areas will turn into black, I think that a private settlement with the auction house and the sellers will be eventually looked for and the insurance will step in. The papyrus will disappear and nothing about it and the settlement will ever reach us, average citizens and real co-owners of the Sappho fragments, because current legislation protects the privacy of these types of “discreet” (i.e., secret) agreements. In other words, current legislation protects wealthy anonymous collectors, even wealthier auction houses like Christie’s, and the throng of experts working with them. Certainly that legislation does not help fostering a cultural environment in which ancient manuscripts are studied and protected by academics, dealers and collectors with higher ethical standards than those this story has brought to light.

It was in the air, and finally it has become official yesterday:

It was in the air, and finally it has become official yesterday: