What do Sappho and the wife of Jesus have in common? Both figures are attested, directly or indirectly, in papyri in the hands of anonymous private owners who are reported to have asked two prominent scholars, Dirk Obbink (Oxford) and Karen King (Harvard), to study and publish them. Now, although issues of provenance may certainly arise for pieces in public collection, they become especially delicate in case of pieces from private collections. As I have noticed writing on the London Sappho in a post a couple of months ago, there are not shared, clear guidelines for deciding what to do in such cases, but there are national and international laws to be respected and there are also professional associations’ recommendations to be followed if you are a member. In practice, as I will try to explain, problems start as soon as you ask yourself what legal ownership of antiquities, papyri in this case, means and implies.

How could papyrologists verify that a papyrus has been exported legally from Egypt and then legally purchased by a dealer or collector? This question has kept me busy since a while. The UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property of 14 November 1970 is the main guide and threshold to be taken into consideration. It is clear what the convention establishes in principle, but the single nations’ ways and timing of reception varied. Article 21 of the Convention explains that it “shall enter into force three months after the date of the deposit of the third instrument of ratification, acceptance or accession, but only with respect to those States which have deposited their respective instruments on or before that date. It shall enter into force with respect to any other State three months after the deposit of its instrument of ratification, acceptance or accession.” While some nations proceeded to ratification, acceptance or accession immediately, others did not. The United Kingdom, for instance, accepted the convention only on 1 August 2002. The United States of America accepted it on 2 September 1983, with important postils underlining rights of interventions (e.g. “the United States understands the provisions of the Convention to be neither self-executing nor retroactive”). In sum, although the Convention certainly is an ideal threshold since its promulgation, there have been different ways in which its principles have been applied in practice.

And what about Egypt’s legislation? This regulated the ownership of antiquities well before the UNESCO convention and its enforcement: a law on the protection of antiquities was issued on 31 October 1951 (law no. 215, emended by laws no. 529 of 1953, no. 24 of 1965, and now superseded by law no. 117 of 1983, emended in 2003). This law set very clear rules forbidding private ownership of movable and immovable antiquities. It also established that whoever accidentally finds movable and immovable antiquities must declare them to the competent authorities (art. 9-11). To my mind this means, for instance, that according to the Egyptian law the finding, and following selling and export of the codex Tchachos (aka Mr Judas gospel), were illegal, since they started in the seventies of last century, i.e. twenty years after the promulgation and enforcement of law no. 215.

I wonder then, should the past and present Egyptian legislation on the protection of antiquities have legal and ethical relevance when deciding about publishing papyri, or not? My personal answer is ‘yes’. Other views on this?

A careful check on the original documents in the hands of the collector is clearly essential; I would not be able to recognize if a modern document is faithful and formally legal, therefore I will need the help of law experts. A colleague I have consulted suggests I may ask the owner to provide an official declaration (an affidavit) on provenance, but would you trust someone you meet for the first time and probably via email or the phone? Then a new problem will have to be solved in case of publication: does my word, the word of an academic, or that of a publisher or a journal’s editorial board suffice for the public to be assured that the provenance of a papyrus is legal? I remember a similar question was posed and never answered in the Oxford forum on the new Sappho poems. I trust my colleagues, but should our professional practices rely only on academic trust and our good behaviours? In other words, what kind of data should we provide in publications on the acquisition of such papyri?

In the case of the London Sappho, Dirk Obbink does not provide any detail on acquisition circumstances and documents in the final publication of what is now called in papyrological language ‘P. Sapp. Obbink’, just out (Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 189, 2014, 32-49); the merging P. GC. inv. 105, from the Green Collection, is also published without details about its provenance and acquisition circumstances by Obbink, with Simon Burris and Jeffrey Fish (Baylor University), in the same issue of Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik (pp. 1-28). In sum, we are left with the short statement that the provenance is legal given in the Times Literary Supplement, and with the unforgettable details, freely available on line, on how the Green collection has been formed in these years (see my post Papyri, the Bible and the formation of the Green Collection, and Brice C. Jones’ old post on odd behaviors in the Green house). Maybe something more will be said in the forthcoming study on the restoration of the papyrus announced by Obbink (p. 32 footnote 2).

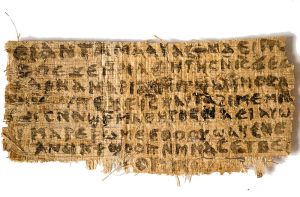

In the case of the Jesus wife’s gospel fragment, Karen King provides the following information (Harvard Theological Review, 107/2, pp. 153-154 that I copy with footnotes):

The current owner of the papyrus states that he acquired the papyrus in 1999. Upon request for information about provenance, the owner provided me with a photocopy of a contract for the sale of “6 Coptic papyrus fragments, one believed to be a Gospel” from Hans-Ulrich Laukamp, dated November 12, 1999, and signed by both parties. [footnote 105: The amount of the price paid was whited out on the copy I was sent.] A handwritten comment on the contract states: “Seller surrenders photocopies of correspondence in German. Papyri were acquired in 1963 by the seller in Potsdam (East Germany).” The current owner said that he received the six papyri in an envelope and himself conserved them between plates of plexiglass/lucite.

The owner also sent me scanned copies of two photocopies. One is of an unsigned and undated handwritten note in German, stating the following:

Professor Fecht believes that the small fragment, approximately 8 cm in size, is the sole example of a text in which Jesus uses direct speech with reference to having a wife. Fecht is of the opinion that this could be evidence for a possible marriage. [Footnote 106: “Professor Fecht glaubt, daß der kleine ca. 8 cm große Papyrus das einzige Beispiel für einen Text ist, in dem Jesus die direkte Rede in Bezug auf eine Ehefrau benutzt. Fecht meint, daß dies ein Beweis für eine mögliche Ehe sein könnte.” The named Professor Fecht might be Gerhard Fecht (1922–2006), professor of Egyptology at the Free University, Berlin.]

If these two documents pertain to the GJW fragment currently on loan to Harvard University, they would indicate that it was in Germany in the early 1960s. [Footnote 107: The second document is a photocopy of a typed and signed letter addressed to H. U. Laukamp dated July 15, 1982, from Prof. Dr. Peter Munro (Freie Universität, Ägyptologisches Seminar, Berlin), stating that a colleague, Professor Fecht, has identified one of Mr. Laukamp’s papyri as having nine lines of writing, measuring approximately 110 by 80 mm, and containing text from the Gospel of John. Fecht is said to have suggested a probable date from the 2nd to 5th cents. c.e. Munro declines to give Laukamp an appraisal of its value but advises that this fragment be preserved between glass plates in order to protect it from further damage. The letter makes no mention of the GJW fragment. The collection of the GJW’s owner does contain a fragment of the Gospel of John fitting this description, which was subsequently received on loan by Harvard University for examination and publication (November 13, 2012).]

In this case, there is a clear effort to give us as more information as possible. Nonetheless are we all satisfied with this level and kind of information? Are they enough to clear issues of provenance and acquisition?

So far on legal provenance and publication of data related to the modern history of the papyri: are there any other, further questions to be considered? Indeed there are, and very important ones.

You are going to inspect a papyrus and will have to decide if to study and publish it, or not: your decision will have consequences on the value of it. For the sake of clarity, let’s consider the specific case of the wife of Jesus fragment in the light of this panorama. We have seen that the price paid for this and the related batch of papyri in 1999 was prudentially whited out in the purchase documentation sent to professor King. Another interesting piece of information on the world of antiquity collectors and dealers is given in an article published in 2012, which I re-read for the occasion. Karen King recounted to the Smithsonian magazine the story of the first approaches from the collector. She was contacted first in 2010, but left the inquiry unanswered until when in 2011 a second email followed (A. Sabar, ‘The Inside Story of a Controversial New Text on Jesus’, The Smithsonian.com, 18 September 2012 available at http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-inside-story-of-a-controversial-new-text-about-jesus-41078791):

In late June 2011, nearly a year after his first e-mail, the collector gave her a nudge. “My problem right now is this,” he wrote in an e-mail King shared with me, after stripping out any identifying details. (The collector has requested, and King granted him, anonymity.) “A European manuscript dealer has offered a considerable amount for this fragment. It’s almost too good to be true.” The collector didn’t want the fragment to disappear in a private archive or collection “if it really is what we think it is,” he wrote. “Before letting this happen, I would like to either donate it to a reputable manuscript collection or wait at least until it is published, before I sell it.”

This collector loves his fragments, maybe he believes they increase his proximity to ancient culture (Lucian’s The Ignorant Book Collector is keeping coming back to my mind, it must be that I used it for teaching recently), but he is also well aware of their price – as you read above – and the money he may potentially make and spend in different ways, such as sending the kids to Harvard or Oxford, taking many holidays to the Maldives, buying a house in Tuscany, or maybe purchasing more papyri, in view of his great passion or in case he is a dealer himself. The value of this piece, and I believe also of the rest of the small collection deposited for study in Harvard, has certainly increased from 18 September 2012 (the day the Jesus’s wife fragment was presented in Rome at the International Congress of Coptic Studies) onwards. In short, this was a lucky strike for the owner, whatever his intentions were and are now. At present, it seems that he will leave the papyrus in Harvard for scholars’ consultation, but ownership, and possible future gains, will stay with him, unless he will establish to donate the papyrus to an institution, as he said was an option, or – why not? – to the country the fragment comes from. This reminds me that unless I have missed something, we are still waiting for the Tchachos codex to be moved to Egypt since almost a decade by now. But this is another story, one where a lot of money were involved: read Neil Brodie, ‘The lost, found, lost again and found again Gospel of Judas’, Culture Without Context (19) 2006, 17-27 if you wish to refresh your memory.

It should be mentioned that not only the anonymous owner, but also other people had some benefits from the publication process, directly or indirectly, and in different measures and ways. I imagine the current issue of the Harvard Theological Review will sell more than usual; the production of documentaries (like that of the Smithsonian that you can watch in the French version on YouTube) and other media releases should have involved some money too; academics and other experts who took part to the research process had a return in terms of publicity, career, impact, and consequent visibility, for instance, for potential University donors or, in case of technical laboratories, for similar commissions. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with all this, but I wish to stress that although to publish a papyrus or any other ancient artefact legally owned by a private collector is certainly legal, it is not a neutral act: it has consequences on the price of an ancient object in private hands, and involves a number of professional and ethical questions that cannot be ignored, as I tried to show.

Among these questions there is also that of the advancement of knowledge. It is clear that especially when presented with texts of such interest and importance, academics feel the peril to lose the occasion to bring relevant ancient sources to light causing detriment to research. There is some truth in this argument. Imagine Karen King or Dirk Obbink were not fully satisfied with the legal status of the papyri in question, or with the possibility to publish details on them: we would know nothing about these new texts (whatever the results on authenticity issues of the wife of Jesus papyrus will be, the source remains in any case important to the scholarly debate: think about the Secret Gospel of Mark). However, I cannot see how knowledge could overcome the laws in case of papyri of dubious provenance, or prevent us asking ourselves relevant ethical questions connected with the exercise of our profession. I would be really glad to read and discuss cogent counter arguments on these last points.

Thank you for this helpful analysis. Scholars underestimate the intellectual consequences of looting: the loss of context, the associations, the findspot etc.

There is too much emphasis on ‘the provenance’. But what do we mean? The pedigree? Who handled it? Or where it was found? Chris Chippindale and I have long argued that we should differentiate between the collecting history and the archaeology. So what is the fully documented and authenticated collecting history for the papyri that you mention?

ZPE needs to tighten up its editorial procedures and adopt an ethical policy related to recently surfaced material.

Pingback: Christology around the Blogosphere

Dear David, thank you for your comments. Papyrologists usually give both archaeological and collecting history when data are available, or they do explain why it is impossible to refer on them. For instance, in our and other collections, it is impossible to give the archaeological history of the papyri since all the pieces were acquired on the antiquity market from the last decades of the 19th to about 1920. Professor King makes a good job giving an attempted archaeological provenance and then information on the collecting history of the piece. What I tried to explain is that referring on the collecting history becomes a hard task especially with private collectors, and that there are not set rules on the way in which these data should be given. It would be hard for me personally to understand what fully documented collecting history means, considering national and international legislation: I personally would adopt a very, very strict view on it but for personal ethical reasons not because of legislation.

Papyrologists don’t have a great opinion of colleagues publishing papyri without giving archaeological and collecting history information: this is a fact.

In my opinion this is the best summary of the issues I have seen. I have added a link to it in the section of my blog on Sappho I am calling ‘Sappho 2014: the Backstory.’

Thank you Stuart!

Maybe you could update taking in the latest developments regarding the real provenance of the wife of Jesus fragment?

Tony, I wish I could! Do you have new information on this, apart that Laukamp has becoming even more elusive than before? I really hope Karen King will reveal the name of the anonymous owner as a recent article in the NYT seems to suggest http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/05/us/fresh-doubts-raised-about-papyrus-scrap-known-as-gospel-of-jesuss-wife.html?_r=0

Pingback: On Institutional Responsibilities and on Gender: Final thoughts on the G of Jesus Wife | Early Christian Monasticism in the Digital Age

Pingback: A New Project: The Early History of the Codex | Variant Readings